Everyone can handle the expat lifestyle when it’s all famous international landmarks, breathtaking cultural experiences, and charming local children giving you presents. But what to do when your day hits the skids and you’re far from home? Last month I had the chance to find out (not once, but four times), which inspired me to come up with today’s list: the Top 10 Troubles you will face overseas and how to deal with them. I’ve faced every single one of them myself.

1. Car accidents

I used to consider myself a good driver. Then I moved to Africa and promptly crashed my car into inanimate objects four different times in two years. My most recent crash involved a tree, a hungry preschooler in the backseat crying for pizza, and my least favorite gear: reverse. The quote to repair the bashed rear of the car seemed enough to cover the entire cost of a new car, but everything car-related is more expensive in Botswana and there aren’t many budget repair options.

What to do: Take Botswana’s public transport combis for awhile, until you realize that spending 45 minutes to go three miles isn’t a good idea. You can also make sure you have auto insurance, although local companies may have unfamiliar procedures and obtaining quotes can be a frustrating experience. Reviews are also mixed on how well the company of your choice will pay up if you do get dinged. One solution is to sign up for “worldwide” insurance like Clements, which you can do completely online and pay by credit card. I really wish I had done that before my latest mishap. Instead the car was completely unprotected because my insurance had lapsed due to a problem with our local bank account, which brings us to the next item on the list.

2. Banking problems

Getting money overseas is more trouble than people think. It helps to have a checking account (like USAA) that doesn’t charge withdrawal fees from foreign ATMs and a credit card that doesn’t charge a few cents every time you make a purchase abroad (those 40-cent charges add up quickly). But even with these niceties, problems abound. In my last two overseas countries, I practically had to give a blood sample and a lock of my grandmother’s hair in order to open a new local bank account. Even after crossing that hurdle, online banking never really worked: doing just about anything still required a physical visit to the bank headquarters across town and a long wait in line. Finally, for no reason whatsoever, our local bank account in Gaborone just froze. Since the preferred form of payment for almost all bills in southern Africa is through local wire transfer, I left a trail of overdue bills in my wake until I could visit each vendor individually in person with wads of pula.

What to do: Beats me. If someone has a solution for cheaply and easily transferring money from a bank account in your home country to one in your adopted country, by all means share it. In the meantime, I will continue to pass out cash like a rock star to everyone from the pediatrician to the dentist.

3. Pet emergency

Our beloved yellow Labrador has made the move with us to three different continents and is part of the family. So when she goes down with an illness, it knocks our whole house into a panic. A few days after the car accident, we came home on a Saturday night to find that our dog had thrown up all over the house and was weak and shaking in the corner. We packed her to the vet in a rush while a poorly-capped bottle of tequila we had taken to a Mexican-themed party that afternoon leaked all over the trunk en route. (There is nothing quite like tequila and dog vomit to really class up a vehicle.) Luckily our dog was diagnosed with a simple case of “eating something rotten” and was all better by morning. But if it had been Botswana’s dreaded tick fever, we would have gotten her help in time.

What to do: It’s imperative to have a relationship already established with a good vet in town. Twenty-four hour pet clinics are far from a global norm, and the only reason we could have our dog seen at an odd hour was by calling the vet personally and asking her to meet us at the clinic. Take your dog in when she is well and healthy so the vet remembers you and is willing to heed your plaintive cries for special treatment late at night on a weekend.

4. Kids’ health issues

Of course, the only thing worse than a pet health emergency is one involving your kids. An unfamiliar healthcare system and the possibility of sub-par medical care ranked right at the top of the list of “cons” when deciding whether we should move to Botswana with children. (And of course, it’s not only children who may face dire illness overseas.) Luckily, we are only a 45-minute flight away from world-class hospitals in Johannesburg, and we are good friends with a trusted pediatrician in town. But those reassurances go out the window the second your child seems to be in trouble and you remember that you can’t call 9-1-1.

A few days after the dog drama, we took our 6-month-old baby to the hospital because I didn’t like the sound of his cough. Let me just say that 1:00 in the morning at an emergency room in Gaborone is not the time or place where Botswana shines the brightest. (This could probably be said for any country.) The doctor was wearing a very stylish buttoned-up shirt but had never heard of whooping cough and was unduly excited about the possibility that our baby had asthma. He accused my husband of being a secret smoker and then sent us home with a bag full of prescription medications, including cough syrup meant only for children older than six. When I visited this exact same emergency room one afternoon last year with a bad migraine, I received extremely professional and competent care. The message: make sure your health emergencies only occur during daylight hours.

What to do: Because you can’t actually control when emergencies will occur, have a back-up resource. Our doctor in the U.S. is on speed dial for when trouble hits, which works well because middle-of-the-night emergencies in Botswana happen during regular office hours in California. She advised me not to give the medicine and that a steamy shower and salt water bath might be all he needed to settle and sleep. Thank goodness she was right, and the cold passed in a few days. For more critical emergencies in less-developed countries, medical evacuation insurance is a good idea.

5. Utility interruptions

Sometimes the issues aren’t harrowing but merely inconvenient. What about those days when basic services in your new country aren’t exactly what you pictured? Botswana is in the middle of a multi-year drought and water resources are low: this means that our water automatically shuts off for eight hours every Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. Power interruptions have lately ramped up as well, which cut off the electricity anywhere from one to three nights a week, usually just at the moment you are pulling something blazing hot out of the oven or in the middle of changing an especially messy diaper. When we lived in Pakistan, Islamabad had no city water system at all; instead a truck came every few weeks to fill a tank on the roof. We discovered just before leaving the country that the tank we took showers from for two years was the final resting place for a dead bird, which I can’t imagine was doing much for body and shine. Even in well-developed countries without such extremes, you may have to get used to tiny washing machines and drying your clothes in nothing but good old-fashioned sunshine.

What to do: Plan ahead. We have to time our showers and baths carefully, hitting that sweet spot of water plus power. We also keep the grill tanked with propane so we can still make dinner when the power’s out, and flashlights and candles are strategically placed throughout the house at the ready. Sometimes you also have to get creative. After an unusually long water outage last week, we scooped a few buckets from the pool so we could flush the toilets. (There’s a reason I get a 20% bonus on top of my salary every year in Botswana for “hardship pay” and that day I earned it.) Above all, try to roll with it. If you can see the bright side of your house being plunged into darkness unpredictably a few times a week (less screen time for the kids!), all the better. After all, how many people can say their toddler’s first word was “generator”?

6. Visa and permit hang-ups

Just about the time you’ve eased into your new home and are really enjoying the country and lifestyle, you may get hit with that dreaded expat quandary: visa and work permit issues. When I lived in Pakistan from 2009 to 2011, Americans weren’t exactly popular with the host government, and getting a visa longer than three months was almost impossible. Finally we discovered the cause: I had been put on a “list of suspicion,” targeted as possible CIA by the ISI, Pakistan’s intelligence service. It was unclear to me exactly how I had time to do sneaky CIA stuff while working 60 hours a week on a donor-funded project and supervising a team of 10. But when the ISI calls, you show up. I was interviewed by a young agent who grilled me about my job only briefly before asking if he could send me his short stories. It turns out he wasn’t after government secrets so much as feedback on his creative writing. I dutifully waded through dozens of pages of tortured prose and received a one-year visa not long after. (Coincidence?)

What to do: All the planning in the world won’t necessarily solve this one, but you can keep your application files orderly and hit all the deadlines at least. Also keep in mind that the expat experience shouldn’t even be attempted in some countries without you or your partner securing a job (or student status) first. In Botswana, you should have employment in hand and a company ready to sponsor your work permit process the minute your plane lands.

7. Paperwork hassles

A precious work permit is not the only document you may need overseas, of course. Although I’m very grateful for email, scanners, and electronic signatures (how did expats pay their taxes before the internet?), sometimes you just can’t take shortcuts. To get the divorce papers from my first marriage notarized while living in Islamabad, I had to trek to the U.S. Embassy and wait in line with 300 Pakistanis trying to visit America. I spent a depressing two hours listening to people crying over visa rejections while pondering whether 33 was too young to already have a divorce under my belt. But I was lucky: I’m told you have to make an appointment one month ahead to see a notary at the U.S. Embassy in Paris.

What to do: Thankfully, most things don’t require your physical presence anymore. Designate a Power of Attorney back home before you move–a trusted friend or family member who can write checks for you and perform other basic functions. And never, ever let your U.S. driver’s license expire lest you find yourself spending endless hours navigating the intricate licensing rules of another country. (My husband had to take a week off work in order to tackle Botswana’s perplexing road test. The good news is that the license lasts for life.)

8. Theft

Security conditions vary widely depending on the country, city, and even neighborhood. Muggings and robberies can happen anywhere, but in an unfamiliar environment they are especially unsettling. I know a newlywed couple whose wedding gifts were stolen out of their new house in Botswana before they’d even had a chance to unpack: newcomers are especially vulnerable.

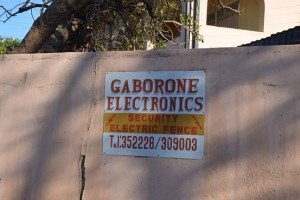

The majority of houses in Botswana’s capital city are surrounded by electric fences to discourage robberies.

What to do: Try to get a sense of the risk before you even arrive and invest in basic security measures appropriate to your new home. In Pakistan, that meant an armed guard at the gate and a “safe haven” room with a heavy bolted door. In Botswana, it’s common to have an electric fence and alarm system, along with special vigilance around the holiday season when robberies peak. Leaving your purse on the passenger seat while driving is a bad idea, and it’s smart to have a back-up credit card stashed somewhere in case your wallet is stolen since it can take days or weeks to receive a replacement by mail.

9. School conundrums

When you become an expat family, you give your children the invaluable education of seeing the world. That being said, you hope they come out the other side knowing grammar and algebra too. Many countries have excellent education systems and/or fantastic international schools, but if you have landed somewhere less academically resourced, it can cause your family a lot of stress. Education for special needs in particular may be non-existent. Even when you do find a good school, the fees can be shocking: regular private schools in Botswana easily cost $10,000 annually for a family with two kids, even before the high school years kick in.

What to do: Many companies pay school fees for transplanted employees, as does the U.S. government for its personnel living abroad. If you’re not in that situation, the quality of a country’s public schools should be taken into consideration before moving, if possible. The tax benefits and cost savings of living overseas can offset the higher school fees, but you don’t want to be taken by surprise when putting your budget together. Home-schooling is also an option for some families when local schools are inadequate, but this requires its own significant sacrifice of time and energy. And at least one family I know put a stop to their expat years altogether to get appropriate resources for their autistic son back in the U.S. School issues are one reason why it’s an excellent time to dive into the expat lifestyle when your kids are younger than five.

10. Family matters

When I ask my expat friends the hardest thing about living overseas, one answer comes up again and again: missing family. Holidays, anniversaries, and the birth of children abroad are all joyful occasions that can make you homesick. But it is a different situation altogether when illness or death happens to family back home and you’re not there. Traveling thousands of miles with little warning for funerals can be exorbitant or even impossible, and it can be wrenching to decide whether you should come home when a relative falls sick or is diagnosed with a serious condition. At times like these, the long distance magnifies an already difficult situation.

What to do: There is no easy answer for this one. Skype and phone calls do their part to bridge the gap and keep loved ones in touch, but they don’t let you hug your relative, help with their daily life, or say goodbye in person when the time comes. Regularly scheduled trips home are important, as is the reminder to live each moment you do have together fully. My grandfather died at age 92 while I was living in Botswana, and we had been very close. I felt the loss keenly and was so grateful for the trip I’d taken to see him six months earlier, for each conversation and laughs we’d had together. And being overseas did provide me with one last gift: I received my Christmas card from him in February, one month after his death. Thanks to Botswana’s very slow postal service, I got a surprise note from him after he was gone with a beautiful scrawled “Love, Grandpa” that I will save forever.

When all else fails, remember that the many benefits of living abroad still outweigh the hassles, and that whatever you’re facing will probably make a good story someday. If and when you do move back to your country of origin, you’ll never take its particular comforts and conveniences for granted again.

4 Comments